Ever wonder how much your other half truly cares about you? Ask them to send you a playlist. Nothing reveals true sentiment quite like this.

If you receive an editorial streaming playlist in return, then I hate to break it to you, but it’s over; get back on the dating apps. Alternatively, if they send one back with custom artwork, a unique title, and detailed reasons for including each track, then boy, you’ve got a keeper.

If they make a physical copy? Put a ring on it; you’ve found the one.

Why my insistence on this method? Music says as much about our personalities as any other cultural identifier possibly could; tattoos and clothing included. If someone both understands your music taste, and feels comfortable enough to express theirs to you, then they know and love your soul in a way that few others could.

And this is a relatively new phenomenon, one I’d argue that we’re still acclimatising to. Music, as social expression, was once locked to the shelves of our vinyl collections, or the rare moments shared at live concerts. Now, thanks to digital world we’ve constructed over the past two decades, and more importantly, the social media through which we experience life, music has become an unbroken soundtrack that surrounds us wherever we are. Yet, whilst social networks are increasingly more musical and dynamic in nature, the music platforms, where we consume, are tellingly resistant to incorporating the same social elements.

Listen on Spotify or Apple Music, and you’re presented only with that which the artist, label or platform is happy to divulge - artwork, lyrics, maybe a short bio. It feels sterile and restricted, especially when contrasted with the wild west of the rest of the digital cosmos. On DSPs, algorithms trump editorial curation, AI beats out human interactions. The fan is noticeably absent, and the far-reaching trail of user-generated-content (UGC), which elsewhere becomes as much a part of the story of the song as the inspirations behind the recording, is tellingly lacking.

There are two stories behind every song; that which inspired it, and then the way the audience receive it. Omitting one of them increasingly feels naive and bizarre.

The social-void on DSPs can, in part, explain why the next generation of listeners is straying away from streaming platforms; instead opting to consume their content via digital-worlds driven by collaboration and co-creation.1 TikTok, Roblox, Fortnite, and even to a certain extent, YouTube, all recognise and encourage UGC to slot purposefully alongside that provided by the original artist. This current generation of 14 - 23 year olds are the first truly raised online, more used to ‘logged on’ than ‘logged off’, where they’re accustomed to social commentary and co-creation being part and parcel of the experience; it’s a non-negotiable.

I’ve never much bought into the concept of a singular ‘metaverse’, built by a well-funded, socially avoidant Silicon Valley bozo. Rather, I buy into the idea that we’re essentially already living in it; it’s within every WhatsApp group chat, every YouTube comment section, every Discord server. The vast majority of our digital experiences, be it a meme, or TikTok, or a song, have some essence of the social to them - all of us stitched together by these invisible wires that both connect and divide.

Content (Daniel Ek’s own word for music, not mine2) when presented without UGC, reads like a foreign language to this next batch of fans. If it can’t be visibly remixed, reacted to, and repurposed, then it may as well not exist. It’s why in order to ensure the survival of streaming, it must be made social.

There’s a lightbulb moment in the journey of every music-tech entrepreneur, when it dawns on them that the single most important music-orientated advancement of the past thirty years was MySpace. Often followed by a whole lot of soul searching and frustration, before an inevitable pivot. A solution to a problem that seemingly didn’t exist; so perfectly executed that it set the tone for everything in the music industry since the turn of the millennium. Music and fandom as social currency.

Two clear product features; the MySpace profile song, and top eight friends, allowed for the display of music taste as cultural identity to enter the 21st century. What was once reserved for band t-shirts, vinyl collections and tattoos, became front and centre of our blossoming digital personas.

As a teenager, I vividly remember the pride (and occasional anxiety) I’d experience in routinely altering my MySpace profile song, ensuring it was aligned with my current mood, tastes or even friendship groups. Similarly, while the top eight friend feature was often a source of much consternation, it also allowed for artists to curate context in a way that the much-despised algorithmically generated ‘Fans also like’ could never dream of doing. Likewise, Fall Out Boy using it to showcase label mates springs to mind.

There’s no doubt that the success of MySpace was partially down to the integration of music within the social experience at the core of it. Yet two decades on, it feels like we’ve regressed; accepting social-flatness as the norm when it comes to our consumption of music. The vibrant UGC world that surrounds every artist and song, exists at arms length, on other apps, and as such, the new fan votes with their feet, and strays.

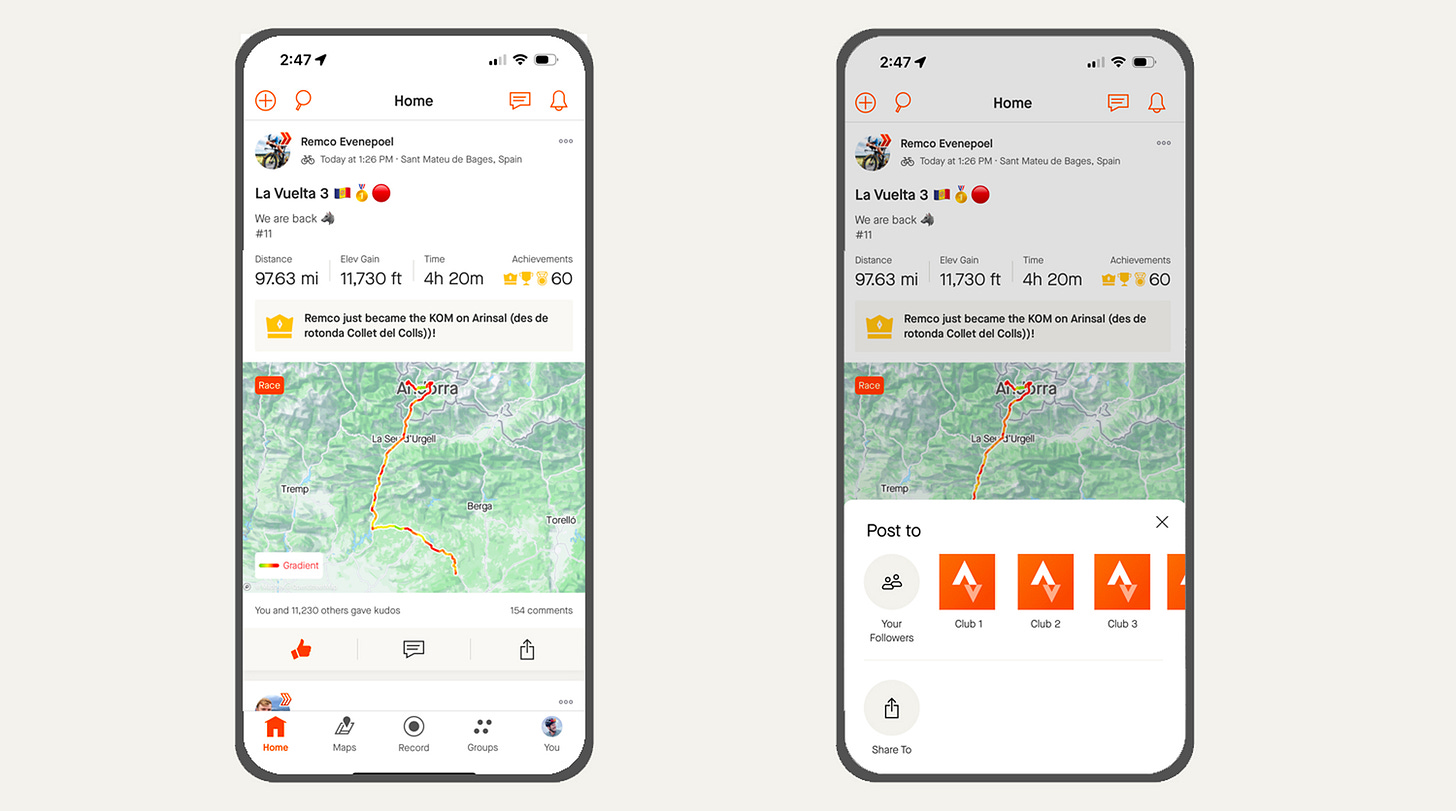

As the rest of the internet and applications (appternet) embraces social as central to the user experience, music streaming services purposefully present content within walled gardens; the UGC blossoming beyond eye-sight. Whether I’m going for a run (Strava)3, reading a book (Goodreads), watching a film (Letterboxd) or just capturing moments (Instagram) of my day-to-day, I’m actively encouraged to make it social. All of these apps treat it as if I’m tearing a page out of a diary that I didn’t realise I was keeping - so that I can share, where comfortable, pages with those I allow to peek into my existence. Why can’t music be the same?

As Kyle Chayka’s brilliant Why I Finally Quit Spotify surmises, “Spotify does not seem to care about your relationship to “your” music anymore.”4 The longer I spend on the app, the more difficult I find it to disagree.

So why this refusal from DSPs to become social?

I’d pin it on the marketing funnel concept being entirely redundant, and many of these platforms having a misguided self-awareness as to their positioning within this disjointed, outdated funnel. A stream is not a satisfactory bottom-of-the-funnel goal for an artist promoting their music, rather where they really win is if they can draw a fan into their world (I’ve resisted saying community for as long as I could). All of the content that surrounds an artist is in a continual state of orbit; what’s an entry point for me, is an end-state for another user.

If we should’ve learnt anything from the turn of millennium earthquakes that forever altered the landscape of the music industry, it’s that if you don’t provide consumers with what they desire, they will go elsewhere to find it, even if it’s to the detriment of artists.

For artists to succeed, they have to be ever-present, ever-visible across our digital experience. Hitting every touch point, ensuring that the fan can begin their journey from any point possible, and move sideways, upwards, downwards, cross-platform, IRL to URL and in-reverse - resulting in a re-shaping of the funnel to a sphere, with superfandom at the core.

We’re entering the era of hyper-performative fandom. Where the display of our passion is as important as our love of the artist itself. This goes some way to explaining the chasm growing between the top selling events, and the rest of the live industry. Friends of mine who previously would never have expressed interest in going to see either Taylor Swift or Oasis, yet acting out every moment of their fan journey - from the elation of the ticket purchase, to the attendance of the shows themselves. The internet is a stage on which we all perform, and there’s no driver of FOMO quite like social media; did you actually go to the event if you didn’t document it?

Where would Brat be without the memes? Imagine listening to Harlem Shake or Black Beatles without the context of the accompanying viral trends? Kendrick Lamar’s Just Like Us would have had a fraction of the impact if released twenty years ago; yet with the ability to slice it up and meme-ify every line, it became the undisputed song of the year. It shouldn’t take me being perpetually logged on across the plethora of apps in order to know this. Are these stories not fundamental to the culture of the music itself? Yet open your streaming app of choice, and this crucial backstory is alarmingly missing.

The rise of toxic fandom5 is partially driven by the social flatness of streaming. Those fans for whom recognition is a key part of their fandom feel driven into ever-extreme, performative acts of dedication to justify their status. Camping outside of gigs for days in advance, the rush to the barrier, the documenting of it all - it’s filling a void that they feel is missing. I’m not for a second condoning the stalking and harassment that certain artists are faced with, however I perhaps naively hope that if we embrace what begins as passion from a fan, earlier on in the journey, and allow it to flourish in a way that the artist is comfortable with, perhaps we can avoid some of these uncomfortable and unacceptable end results.

What’s more, these should be monetizable moments for artists, especially on platforms that seek to drive the value of their actual copyright to zero. Let’s learn from gaming and live streaming, where fans will happily exchange a few dollars each month, in order to be recognised as a key supporter of the creator. The first step towards fixing streaming is understanding that some fans are perfectly happy to pay more, whilst some are content with all of the music, for essentially nothing in return. Right now we’re spoiling the disinterested fan, and ignoring the one crying out for more.

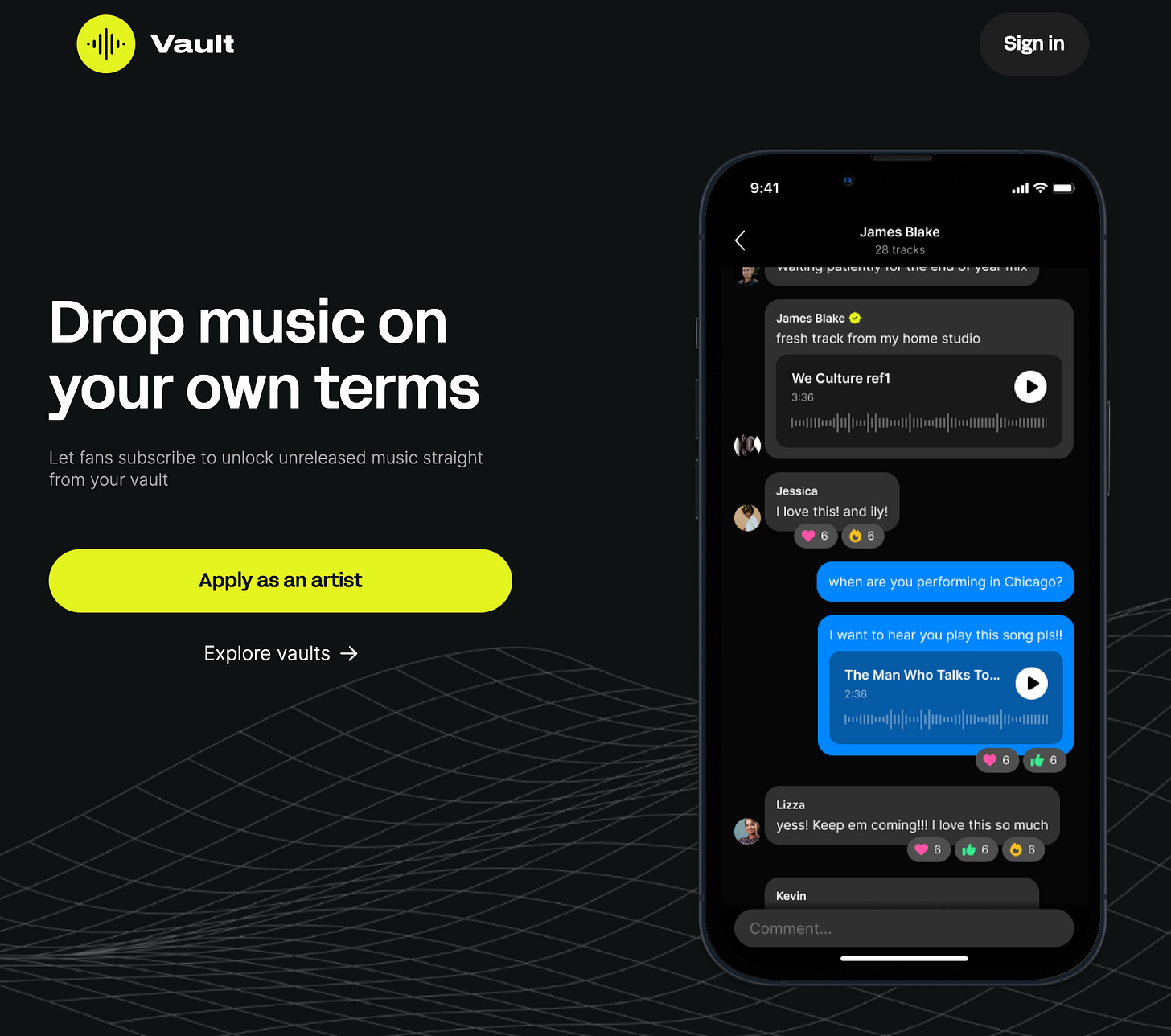

Earlier this year, and to much fanfare, James Blake announced he was helping launch a new direct-to-fan platform, Vault.6 At the core of the offering was the ability for artists to share unreleased demos and early recordings, yet to my mind where the real value existed, was in the chat section, bringing together the most passionate, knowledgable and engaged fans of Blake, into a single conversational space. There was no corner of the internet more clued up on the world(s) surrounding Blake, than his Vault. Worth paying $5 a month for? If you’re a diehard fan of the artist, absolutely.

Music is free. For all intents and purposes, we’ve accepted that now. Whether it’s free via a near-meaningless £10 a month subscription, or you simply pay via your time through advertising, removing the point of purchase, and driving fees into the ground, it’s all meant that time and knowledge has become a more valuable currency than the cents which we exchange for access. Let’s make that mean something.

This is where I should clarify that I don’t see these elusive superfans as a water-soaked sponge, ripe for squeezing, like many of the major players in the music industry increasingly do. I’m not interested in a 13th vinyl variant, land-fill merch or demand-based pricing; for all of which the end goal is a less vibrant, more obnoxious experience for all. Rather, I’d prefer to see this proposed social layer monetised, for the benefit of artists. The value is in strengthening the connection between fans through and recognition and experience.

Streaming services should be approached less like an all-you-can-eat-buffet, tables stacked high with gluttonous copyright offerings of every genre, and instead handled more like a scrapbook, treating the music as prompts to a world we can make our own. Allow us to colour these pages with our own memories; make me feel intimately part of this universe; a co-creator in the stories - not merely a passerby.

Artists themselves are already strikingly aware that they’re only painting half the picture when it comes to the music they release; it’s a promotional cliche but the ‘this song is yours now’ line should ring true, yet in a world where all digital content is ripe for contextualising, remixing and repurposing, streaming services refuse to acknowledge this crucial part of the fan journey. I’d compare listening on DSPs to being at a concert surrounded by thousands of fans, yet everyone has their eyes and mouths sewn shut; frighteningly unaware of the joy and emotion thriving alongside them. With every Friday that comes around, I grimace at the number of artists choosing to take to socials to share thanks to largely faceless playlisters, often ahead of showing gratitude to their fans, the real engine rooms of their projects.

It’s no surprise that those artists that have adopted community as a core value of their projects, have thrived over the past few years. Be it Taylor Swift’s friendship bracelet swaps, or Fred Again treating his gigs like a gathering of old pals; the start point is the music, the end goal is a shared world; all the more enticing and fascinating for it. And the artists ultimately gain from it.

So what exactly do I mean by making streaming social?

Here are a few easy wins for starters:

Turn users into fans. Make the fan profile customisable and enjoyable. The user profiles are the most underserved feature of DSPs - add a sense of pride to them, and make them a home for showing off music taste.

Embrace taste. Fans are curators, whether making a short-form video about their favourite new songs, or simply adding ratings to new releases; allow taste to become front and centre of every fan experience. And while we’re at it, ditch the public stream counts; meaningless garbage.

Encourage narrative. Allow artists to tell the story of the audience experience; comments on songs, visual reactions, networked playlists. Build worlds around songs, don’t restrict them.

Reward sharing and collaboration. The second most underserved feature of DSPs is the share function. As I touched on at the start of this piece, sharing music is beautiful, freeing and easier than ever. Let’s make it happen within the apps.

Music isn’t just something we consume; it’s something we experience, share, and shape together. It’s not background noise—it’s the heartbeat of memories, the soundtrack to our lives. To strip music of its social context is to drain it of its soul. Streaming platforms have forgotten this, and in doing so, they’re alienating the very fans that drive the industry forward.

If we want music to matter again, we need to give it back to the fans. We need to make streaming feel like what it really is: a collective experience. It’s about more than algorithms spitting out recommendations—it’s about connection. It’s about creating a world where music isn’t a lonely, sterile transaction, but a shared celebration of life’s highs, lows, and everything in between.

Fans don’t just want to listen—they want to belong. And when we give them that chance, when we finally make streaming social, we’re not just preserving music. We’re amplifying its power, allowing it to transcend platforms and playlists and truly become what it’s meant to be: ours.

Now… about that playlist…

https://www.midiaresearch.com/blog/social-is-the-new-streaming-but-the-cracks-are-already-showing

https://mixmag.net/read/spotify-ceo-daniel-ek-creating-content-controversy-news

https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/sep/08/goodbye-tinder-hello-strava-have-hobby-apps-become-the-new-social-networks

https://www.newyorker.com/culture/infinite-scroll/why-i-finally-quit-spotify

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/c1jd0e0ydywo

https://variety.com/2024/music/news/james-blake-vault-launch-streaming-royalties-1235947937/